Our research is in interdisciplinary fluid mechanics, and we specialise in the interaction of fluids with solid bodies; in particular, those that lead to counter-intuitive flow phenomena and the formation of coherent flow structures. Our research has three overarching themes: (A) Biological flows, (B) interfacial and multiphase flows, and (C) wave-structure interaction. Our research methods are characterised by the use of analytical, numerical, and physical modelling.

Biological flows.

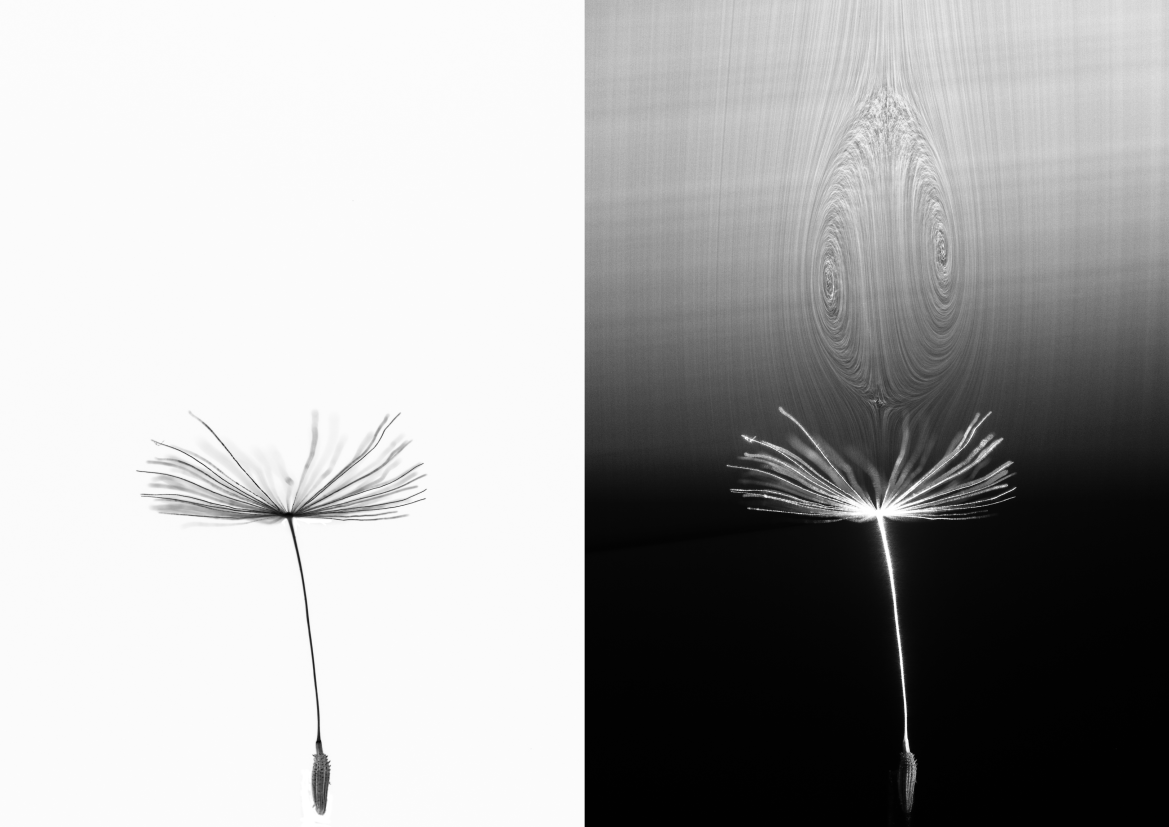

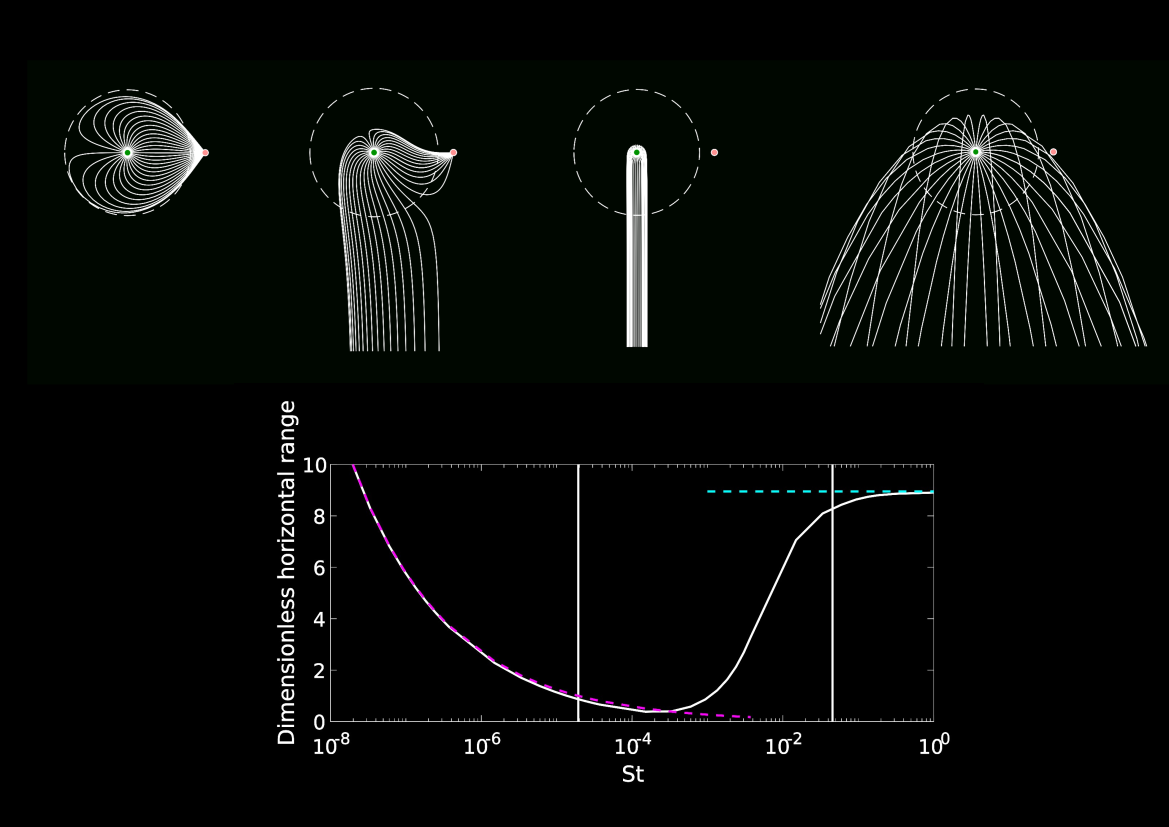

Evolution finds ingenious ways to achieve locomotion through fluids at a wide range of Reynolds numbers (Re): from corkscrewing spermatozoa to the autorotation of maple seeds. Our research focuses on the interplay between low- and intermediate-Re regimes, where we aim to uncover the convergent hydrodynamic strategies to propulsion that nature has evolved.

Evolution finds ingenious ways to achieve locomotion through fluids at a wide range of Reynolds numbers (Re): from corkscrewing spermatozoa to the autorotation of maple seeds. Our research focuses on the interplay between low- and intermediate-Re regimes, where we aim to uncover the convergent hydrodynamic strategies to propulsion that nature has evolved.

Our research on the flight of lightweight seeds uses analytical (boundary integral methods), numerical (direct numerical simulations), and physical modelling (wind tunnel tests) to uncover their incredibly efficient flight mechanism. Our groundbreaking research revealed an entirely new class of vortex, which enhances the flight capacity of the seed. We aim to explore the interplay between the two Re regimes, which will uncover novel strategies for locomotion, and may underlie weight reduction and particle retention of biological and man-made structures. This is of fundamental importance to the navigation of microrobots used for human diagnostics and offers a particle capture solution to the microplastics that litter the Earth’s oceans.

Interfacial and multiphase flows.  When two or more phases meet, the resulting interface forms a capillary surface such a bubble, drop, or liquid bridge. Our research on drops and liquid bridges focuses on the effect of the contact line (the curve forming the triple fluid-gas-solid interface) on the dynamics of the capillary surface. Our research on multiphase flows explores the dynamics of bubbles in buoyancy-driven flows and the dispersion of respiratory droplets, with applications for the spread of infectious diseases.

When two or more phases meet, the resulting interface forms a capillary surface such a bubble, drop, or liquid bridge. Our research on drops and liquid bridges focuses on the effect of the contact line (the curve forming the triple fluid-gas-solid interface) on the dynamics of the capillary surface. Our research on multiphase flows explores the dynamics of bubbles in buoyancy-driven flows and the dispersion of respiratory droplets, with applications for the spread of infectious diseases.

Infinite liquid bridges. A classical problem in the study of capillary surfaces is the Rayleigh-Plateau instability, which is responsible for the breakup of liquid jets in kitchen sinks or the liquid bridge that can form between your fingertips. A related type of liquid bridge is formed when you dip your finger into water and pull upwards; such a capillary surface was previously shown to be unstable. Using variational approaches to stability, we proved that Contact Angle Hystersis (CAH) must stabilize infinite liquid bridges. This revealed a completely new perspective on the stability of liquid bridges and has far-reaching implications for the stability of capillary surfaces in general. CAH is found almost anywhere there is a contact line, and many “classical results” may need to be revised in light of our findings. Our future research on this problem will explore how CAH stabilizes classically unstable surfaces, in particular under the influence of vibration (see Vibrating drops). We will seek to unify the variational and bifurcational approach to stability.

Vibrating drops. A related problem of contact lines involves a liquid drop sliding down an inclined solid substrate. Conventional wisdom suggests that shaking the substrate in the vertical direction would cause the drop to move faster downhill or fly off entirely. However, experiments show that drops given enough of a shake can climb uphill, against gravity. But what enabled this climbing was not previously understood. We performed an asymptotic analysis of the governing equations, which revealed the climbing mechanism to be the nonlinear interaction of vibration modes in the drop’s free surface. Our future research will examine the effect of CAH on the migration of droplets over substrates, especially under vibration.

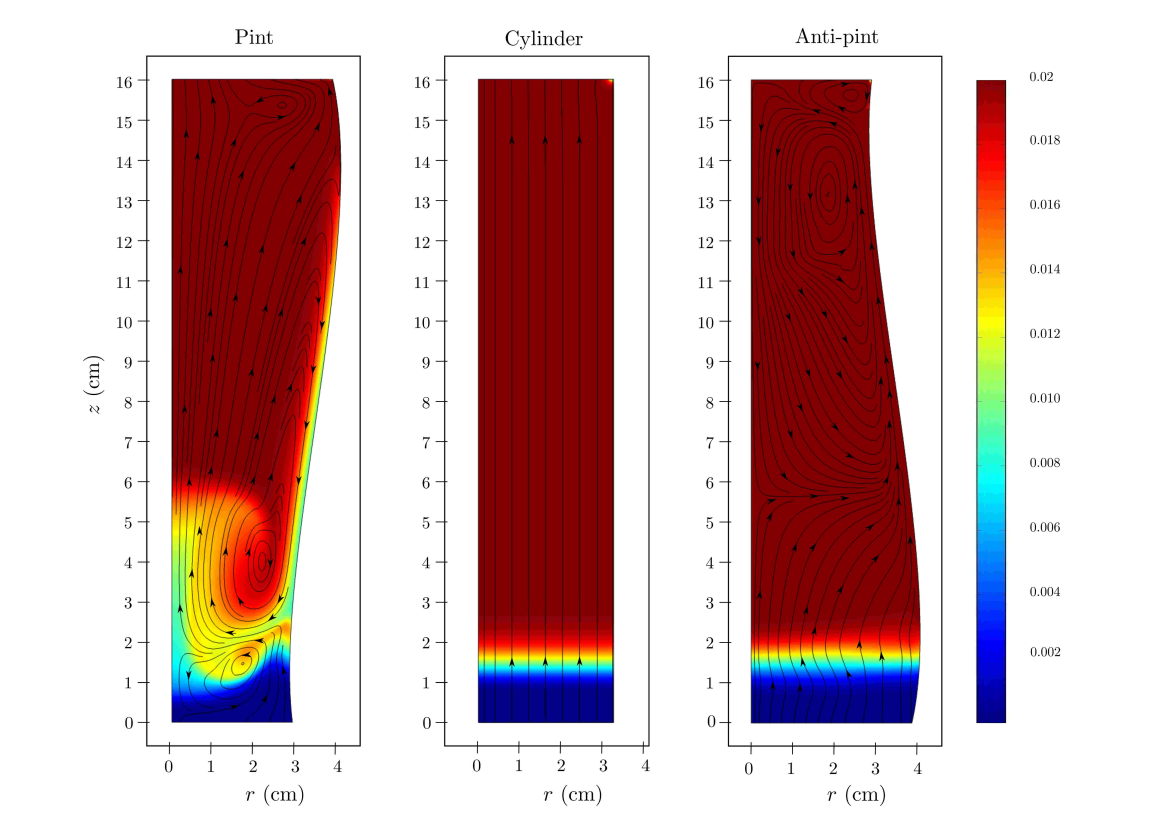

Sinking bubbles.  Our research on multiphase flow explores the motion of two inter-penetrating phases. It has long been known that the bubbles in stout beers sink for about two minutes in a freshly poured pint of Guinness. However, the mechanism that causes the bubbles to sink remained a mystery. Our research revealed that the glass geometry and bubble size conspire to sink the bubbles. Based on this work, we are currently developing a theory of vortex-based microparticle capture, which may be useful to filter microplastics from

the ocean. Our future research will elucidate the mechanism that causes waves (such as the remarkable “Guinness cascade”) to form in multiphase flow.

Our research on multiphase flow explores the motion of two inter-penetrating phases. It has long been known that the bubbles in stout beers sink for about two minutes in a freshly poured pint of Guinness. However, the mechanism that causes the bubbles to sink remained a mystery. Our research revealed that the glass geometry and bubble size conspire to sink the bubbles. Based on this work, we are currently developing a theory of vortex-based microparticle capture, which may be useful to filter microplastics from

the ocean. Our future research will elucidate the mechanism that causes waves (such as the remarkable “Guinness cascade”) to form in multiphase flow.

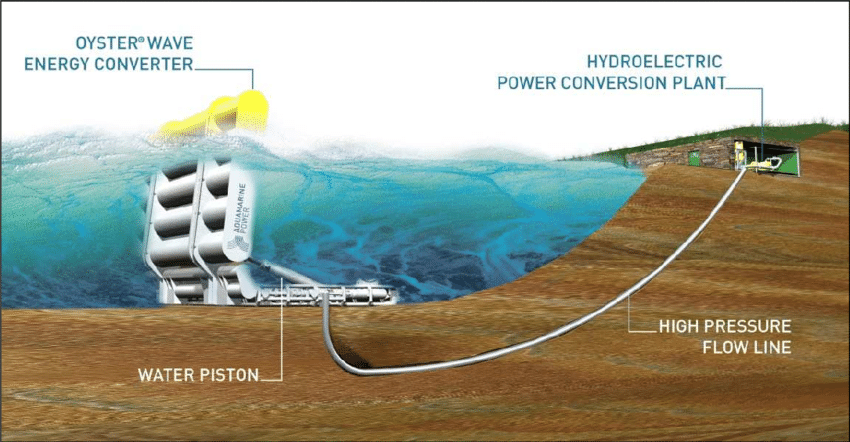

Wave-structure interaction  Wave energy is a promising technology to tackle the energy “grand challenges” facing the planet. Our research in wave energy focuses on the hydrodynamics of Wave Energy Converters (WECs). Simplified hydrodynamic models (Boundary Element Methods, BEMs) are currently used to model the dynamics of WECs. However, this approach neglects viscous effects, and overestimates the power capture of WECs, particularly in resonant conditions. We pioneer a method that includes effects of viscosity in BEM, which leads the way forward for the modelling of WECs, giving realistic power predictions without the need for CFD.

Wave energy is a promising technology to tackle the energy “grand challenges” facing the planet. Our research in wave energy focuses on the hydrodynamics of Wave Energy Converters (WECs). Simplified hydrodynamic models (Boundary Element Methods, BEMs) are currently used to model the dynamics of WECs. However, this approach neglects viscous effects, and overestimates the power capture of WECs, particularly in resonant conditions. We pioneer a method that includes effects of viscosity in BEM, which leads the way forward for the modelling of WECs, giving realistic power predictions without the need for CFD.